| Timeless Nation |

30. "EVERYBODY IS HUNGARIAN...

(Hungarian travellers and settlers in the world)

About one third of the 15 million Hungarians live outside the present frontiers of Hungary. Three million live "abroad" without ever having left their country in the Carpathian basin: their home territory was transferred from Hungary to various succession states by the Trianon Treaty in 1920. We have studied their way of life, art and customs in the various chapters describing the regions of the Carpathian basin.

In this chapter we are looking only at some Hungarians who left the Carpathian basin for various reasons and settled or lived in foreign countries for a considerable period.

The Middle Ages

Several princesses of the Arpad dynasty married into foreign ruling families. We have already mentioned Saint Stephen’s daughter, Agatha, and her daughter, queen Saint Margaret of Scotland (Chapter 5). The daughter of king Saint Laszlo, Piroska ("Irene" in Greek), married to the Greek emperor, was the mother of Manuel the Great (1143-1180), the last great ruler of Byzantium. After her husband’s death Irene retired to a convent in Constantinople where she died and is known today as Saint Irene.

Saint Elizabeth of Hungary, daughter of king Endre II, was married to the Prince of Thuringia. After the death of her husband, Elizabeth dedicated herself to the care of the poor and the sick. Her niece, also called Elizabeth, Princess of Aragon, is known today as Saint Elizabeth (Isobel) of Portugal. We know little of Clemence of Hungary, wife of France’s Louis X in the XIVth century. She was an Arpad on her mother’s side and sister of Hungary’s king, Charles Robert. Her son, John was assassinated when he was five days old.

Queen Saint Hedwig (Jadwiga) of Poland was the daughter of Louis the Great. She inherited the Polish throne after her father’s death (1382). Then she married the pagan Jagiello Prince of the Lithuanians, converted him and his people to Christianity and united the two countries.

We have already mentioned the four Dominican monks who travelled to the borders of Europe and Asia in the XIIIth century in search of the "Greater Hungarian Nation" (Chapter 5).

The XVIth - XVIIIth centuries.

One of the tragic results of the Turkish wars was the deportation of hundreds of thousands of Magyars of all by the Turks as slaves. Estimates indicate that about 2 million Hungarians were subjected to the horrors of slavery. The families were, of course, separated and the children lost their national identity. Many boys were trained in special institution become Janissaries, the Turks’ elite soldiers. They lost all recollection of their birth, name, religion or family.

Brother Gyorgy (George) Hollosi who accompanied a troop of Spanish "Conquistadors" in 1541 in Mexico, lived for 40 years among the Zuni Indians of that country. He converted them and protected them from the greedy Spanish conquerors He died among his Indians who wrote on his tombstone: "Here lies Brother Gregorio Hollosi, brother of all men, who brought light to those who were living in the dark."

Poland’s great king, Stephen Bathori was mentioned Chapter 13.

Among the emigres accompanying Prince Rakoczi to France in 1711 was count Ladislas Bercsenyi, son of the Kuruc commander, Miklos Bercsenyi. Young Ladislas settled in France, founded a hussar regiment which still bears his name and eventually became Marshal of France.

The adventurous count Moric Benyovszky (l74l-l784) began his career as an officer in the Seven Years’ War. Seek further adventures, he went to Poland and joined the Polish freedom fighters against Russia. He fought so well that the Poles appointed him general and made him a count. He was eventually taken prisoner and deported to East Siberia (Kamchatka). Here he rallied his fellow prisoners and managed to capture the fort of the governor and the heart of his daughter. He then commandeered a Russian battleship and set out to explore the Pacific. Having visited Japan, Hongkong and various islands, he spent some time on Formosa (today Taiwan) straightening out the local political situation. He then sailed on and inspected the huge island of Madagascar off the African coast, then still independent and ruled by countless native chieftains. He eventually arrived in France, where he suggested to the king (Louis XV) that he should establish a French colony on Formosa or Madagascar. The king appointed him a general, gave him the title of count and a few promises, and sent him off to Madagascar. Equipped with his titles (and not much else) he landed in Madagascar, befriended some tribes, defeated the others and in 1776 was proclaimed by the assembled chieftains, king of Madagascar. He ruled the island wisely for three years. Among other things he introduced Latin script – with Hungarian spelling – for the Madagascar language. The islanders still use his script and spelling. Then – probably at the urging of his family (he had several, in fact) – he returned to France seeking closer trade and political ties.

This time the French ignored him, so he returned to his native Hungary, where queen Maria Theresa made him a count and appointed him general. But she was not interested in African colonies (she had Hungary, after all . . .) So Benyovszky went to Britain and then to the new Republic of the United States. There he loaded his ship with goods for Madagascar (before they could make him a count and appoint him general) and sailed back to his kingdom. To his surprise, he found a French military establishment there (led probably by a general who was also a count). He fought to regain his kingdom but died during the fighting. Some native legends and street names (and a few generals and counts) keep his memory in Madagascar.

The first Hungarian known to have landed in North Amerika was Parmenius of Buda, a naval officer in the British service (1585). Several Hungarian missionaries worked among the natives of South and North America during the XVIIth and XVIIIth centuries. Colonel M. Kovats was a distinguished officer in Washington’s army during the War of Independence.

Andras (Andrew) Jelki, the enterprising boy from Hungary set out to see the world in 1750 and became a sailor. After having been shipwrecked, captured by pirates and sold in slavery he reached the Dutch East Indies (alive) where he again landed among some primitive natives, who wanted him for (their) dinner, but he "got out of the frying pan" by marrying the daughter of the local chief and eventually became the chief of the tribe himself. Then we find him in Batavia, the capital of the Dutch East Indies, as a prosperous businessman (without his native wife). At a later date we find Jelki in Japan as the Dutch Ambassador there. He died in 1783.

Laszlo Magyar reached Portuguese West Africa (Angola) in the middle of the XIXth century. He began mapping the interior of the colony in Portuguese service and discovered the source of the Congo river. Then the fate of seemingly all Hungarian adventurers caught up with him: he married the daughter of the Sultan of Bihe (Bie) and in due course became the king of the country himself. He died in Bihe under obscure circumstances (possibly during a state dinner…)

The XIXth century

Sandor Korosi-Csoma (1784-1842), the brilliant Szekely scholar, wished to study the origins of the Hungarians. He decided to explore Central Asia first. Being very poor, he travelled to India mostly on foot, equipped only with the knowledge of dozen languages. After an adventurous journey he reached India in 1822. Commissioned by the Indian (British) government to prepare a Tibetan-English dictionary, he spent 16 months in a Tibetan monastery, studying the Tibetan language and literature, completing his dictionary and translating some Tibetan literature into English. He then traveled to various Tibetan towns (the first European to move about in Tibet freely) and studied data concerning possible ties between Hungarians and the Central Asian races.

On returning to India he published his dictionary and Tibetan grammar, which are still the most important source of Tibetan linguistic studies. Having completed his research, he set out to re-enter Tibet and move from there to the area inhabited by the ‘Ujgur" or "Djungari" people, north of Tibet, whom he suspected of being related to the Hungarians. On his way he contracted malaria and died in Darjeeling on the Tibetan border His memory still lives in Tibet. In 1935 he was proclaimed a "Saint" of Tibetan Buddhism. Various Indian scientific institutions preserve his memory.

Sir Aurel Stein, the Asian explorer, was born in Budapest carried out archeological explorations for the Indian (British) government in Central Asia and discovered the so–called "buried cities" in Mongolia.

During the American Civil War many Hungarians, mostly refugees from the Freedom War of 1848-49, settled in United States. Many fought in the Union armies (none the Confederates), such as generals Stahel and Asboth, Coblonels Mihalotzy and Zigonyi and several units of Hungarian soldiers. Agoston Haraszty was a pioneer of Califomia, a wine-grower, a businessman and a diplomat.

General Istvan Turr (1824-1908) took part in the Italian freedom war in 1860 as Garibaldi’s Chief of Staff. He then assisted Klapka in organising the "Hungarian Legion" (cf. Chapter 22). After the Compromise he returned to Hungary and original profession, engineering. He later worked at the construction of the Suez and Panama canals.

Hungarian-born Joseph Pulitzer of newspaper fame served first as a cavalry officer during the Civil War. After the war he became interested in newspaper editing and eventually owned a chain of newspapers. He left his huge estate (about $20 milllon) to a foundation bearing his name and a school Journalism.

Janos Xantus; a self-educated scientist and explorer, discoved several hundred animal and plant species in North America and South-East Asia between 1855 and 1871

The XXth century: science, art and literature

Eight scientists of Hungarian birth received the Nobel P between 1914 and 1976. Only one worked in Hungary when received the Prize (Albert Szentgyorgyi). Of the others Fulop Lenard, Richard Zsigmondy and Gyorgy Hevesy lived in Germany, Robert Barany in Austria, Gyorgy Bekesy and Jeno Wigner the U.S. and Denes Gabor in Britain when they received the award. It was said that if two members of the U.S. Atomic Commission had been absent, the others could have held their meeting in Hungarian. The most eminent of these Hungarian– American scientists was Professor Leo Szilard, who demonstrated the possibility of atomic fission in 1939. With his friend, Einstein, he suggested to President Roosevelt that he should set up an atomic research programme in the United States. The team of Szilard, Teller, Wigner and Neumann – all Hungarians – with the half–Hungarian Oppenheimer and the Italian Fermi constituted the successful Atomic Commission which eventually assured the United States the possession of the atomic bomb.

Todor Kalman, engineer and scientist made himself famous in the U.S. through his many inventions and innovations in the field of aerodynamics and rocket research.

In the field of economics, Hungarian emigres have enriched both "worlds": Jeno Varga was the ]eading economist of Soviet Russia and Gyorgy Lukacs the leading philosopher of Marxism, while Lord Thomas Balogh and Lord Miklos Kaldor were the British government’s chief economic advisors until recently.

Before World War II the American film industry seemed to be Hungary’s only colonial empire. The malicious saying "It is not enough to be Hungarian, you gotta have talent too. . ." was wrong, of course, as quite a few had little talent, only "Hungarian connections". But the names of Adolf Zukor, Michael Kertesz, Sir Alexander Korda, Zoltan Korda and many others assured Hungarian hegemony in the fledgling art of the film. Some film– stars are also of Hungarian birth, such as Peter Lorre, Tony Curtis; Cornel Wilde and Ilona Massey – they were obviously not born with these well–known names. Others seem to be quite proud of whatever they were born with: the Gabor sisters, Marika Rokk, Eva Bartok and many others.

As Hungarian writing is not easily translated, Hungarian writers best known abroad are those who learnt to write in English or German, such as Arthur Koestler ("Darkness at Noon") and Hans Habe. George Mikes has achieved the difficult synthesis of Hungarian humour and British satire. His delightful racial tableaus ("How to be an Alien", "Milk and Honey" etc.) delight everybody (including the people he is satirising).

Lajos Zilahy, a well–known novelist before his migration to the U.S., wrote his controversial historic novels, "The Dukays", in America.

Jozsef Remenyi (1892–1956) was the first great Hungarian American author, essayist and literary historian.

Albert Wass (1908–) was also a noted Hungarian author in Transylvania before 1945. In 1952 he migrated to the U.S., and became a professor of Florida University. His Hungarian and English writings include novels, short stories, poetry, essays and research work of historical, sociological and folkloric nature.

Ferenc Molnar (1878–1952), the most successful playwright of recent Hungarian literature was also a remarkable novelist and author of short stories. His novel "The Boys of Paul Streeet" an exquisite tableau of adolescent life has become a world best seller in many translations. His mystery-drama "Liliom" achieved world fame through its American stage and film-version "Carousel". Molnar settled in the United States before World War II and continued his career as a successful writer for stage and film.

The playwright Menyhert Lengyel noted for his interest in social problems in his dramas written in Hungary before 1914 ("Typhoon"), migrated to the United States after World War I and became a popular film–script writer.

The authoresses Yolanda Foldes and Christa Arnothy in France and Claire Kenneth-Bardossy in the U.S., are well known for their pleasant novels of lighter nature.

Aron Gabor, a journalist living in Germany, presents a staggering indictment of man’s inhumanity to man in his a biographical work "East of Man".

The number of talented authors: poets, novelists, philosophers and historians living abroad and using the Hungarian language in their writings is immense. Their opus represents an important segment of contemporary Hungarian literature, the study which is, however, beyond the scope of this book.

Music is another field where Hungarian participation assumed proverbial proportions. The number of well-known Hungarian conductors living abroad is truly impressive (George Solti, Eugene Ormandy, George Szell and many others). Since Liszt and Remenyi, many Hungarian performing artists especially of the violin and piano have lived abroad, sucb as Emil Telmanyi,: Joseph Joachim, Joseph Szigeti, Johanna Daranyi, violin virtuosos and Geza Anda, the pianist. Miklos Rozsa and Sigmund Romberg have become well–known for their film and operetta music.

In Fine Arts the adage that a Hungarian painter can only succeed abroad has proved true in many cases. Some talented Hungarian artists lived abroad all their creating life, such as Fulop Laszlo, portrait painter in Britain, Ferenc Martyn, avant– garde painter in France, Marcel Vertes, graphic artist, Victor Vasarely, creator of three–dimensional op–art" in France, Gyorgy Buday, graphic artist in Britain, Sandor Finta, the shepherd–boy, who became a famous sculptor, author and teacher, Laszlo Moholyi-Nagy founder of the ‘New Bauhaus" movement, Gyorgy Kepes, professor of Art, M.I.T., and colour woodcut artist Jozsef Domjan in the U.S.A., Amerigo Toth in Italy, Zoltan Borbereki–Kovacs in South Africa and many others.

Hungarians in Australia

The first Hungarian migrants arrived in Australia in the middle of the XIXth century: many of them were ex-officers of the 1848–49 freedom war.

Most of the immigrants before 1930 were single men who married Australian girls and integrated into Australian society The 1930s and 40s saw the arrival of the Hungarian émigré, who left Hungary because of the oppressive atmosphere in Hitler’s Central Europe. They were mostly Jewish intellectuals and businessmen. Hard–working and ambitious, they became respected members of Australian society, but they cherish their Hungarian culture and helped to dispel some misapprehensions about Hungary’s role during World War II. The Australians learned through them that Hungary was, during Nazi oppression, the refuge of the Jews in Europe.

About 15,000 Hungarians arrived in Australia as "displaced persons" between 1949 and 1953. The bulk of them were professional and middle–class people, most of them with families Having met the earlier Hungarian migrants, the two groups could find a common reason why they came to Australia to flee the tyrannies of one kind or the other.

After 1956 another 15,000 Hungarians came. As these were mostly single men, many of them assimilated rapidly. On the other hand, those who came with families – at any period usually kept the Magyar ethnic consciousness in the family a their children learned to appreciate the values of their ethic heritage (through Hungarian schools, Scout and other youth activities), without interfering with their harmonious integration into Australian society and culture.

In the 1960s many migrants came from Yugoslavia: most these were Hungarians, members of the Magyar minority in the country. They ‘usually came with their families and often settled close to each other, assisting each other in a form of co-operative. They have mostly kept their Hungarian identity.

It is estimated that in 1970 about 50,000 Australians had Hungarian ethnic origin. This number does not include the children born in Australia.

Only 0.4% of Australians are of Hungarian origin (or, as the Magyars put it, 99.6% of Australians are of non–Magyar origin) but their involvement in certain professions and occupations tions is well above that rate. They favour occupations in which independence, initiative and imagination prevail and industry assures success.

There were some 50 professors and lecturers at various Australian universities in 1970. Some academics are well-known such as professor George Molnar, who is also a political cartoonist. In their specific fields there are many outstanding scientists, such as the entomologist Jozsef Szent-Ivany, the international jurist Gyula (Julius) Varsanyi, the anthropologist Sandor Gallus, the demographer Egon Kunz, the historian Antal Endrey and Akos Gyory who, at the tirne of his appointment, was the youngest professor of Medicine in Australia. Dr. A. Mensaros, a member of the West Australian government, was the first non-British Cabinet Minister in the State.

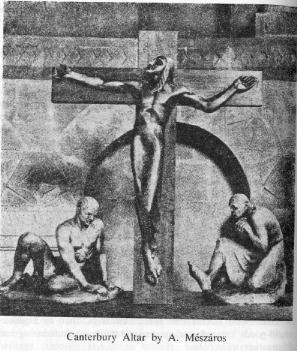

In art and music Australia lacked the attraction of some other countries, thus only a few well-known artists settled here. The conductors Tibor Paul and Robert Pikler are the best known names in music. The Fine Arts are represented by the late Andor Meszaros, the sculptor and engraver, Desiderius Orban, one of the "Group of Eight" (cf. Chapter 25), Judith Cassab painter, Stephen Moor and Gyorgy Hamori decorative artists.

There are many eminent businessmen and architects of Hungarian origin in Australia and the number of small businessmen is immense. It seems that some businesses, such as espressos, small–goods manufacturing and clothing manufacturing are Hungarian monopolies.

In sport, table tennis was made popular by Hungarians. Australian soccer owes its origins and success to Hungarian coaches, organisers, players and patrons. A Hungarian-founded and sponsored team, the "Budapest" (later: "Saint George-Budapest") bas been the most successful team in the country. In chess, Lajos Steiner and other Hungarian players dominated the national championships for two decades. Fencing, a typical Magyar sport, owes its increasing popularity in Australia to Hungarian sportsmen and trainers (G. Benko, A. Szakall).

* * *

There are today almost 2 million Hungarian expatriates who have invaded the farthest corners of the world. Hungarians can be found anywhere – and they usually are. As false modesty is not one of their national vices, they do not conceal their presence nor the fact that they are Hungarians. In fact, their vitality, industry and extrovert friendliness make them more conspicuous than population statistics would suggest. One is tempted to accept the thesis of the Hungarian writer, Mikes: "Everybody is Hungarian…."

There are about 15 million Hungarians in the world today: not quite 0.5% of mankind.

Without them the sun would still rise and life would still go on – but the rainbow would be a little paler, music a little duller, women a little sadder and mankind a little poorer.

| Timeless Nation |